用户:Eggplant1230/沙盒

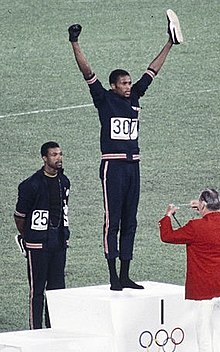

1968年奥运会黑人权力致敬事件是非洲裔美国运动员Tommie Smith和John Carlos在墨西哥城奥林匹克体育场举行的1968年夏季奥运会颁奖仪式上进行的政治示威。史密斯和卡洛斯分别在200米跑的比赛中获得金牌和铜牌后,他们在领奖台上面对他们的旗帜,当听到美国国歌时。每个运动员举起戴著黑手套的拳头,直到国歌结束。此外,史密斯,卡洛斯和澳大利亚银牌得主彼得诺曼都穿著有人权徽章的夹克。史密斯在他的自传“沉默的姿态”中表示,这一姿态不是对“黑人权力”的致敬,而是对“人权致敬”。该事件被认为是现代奥运史上最公开的政治声明之一。

事件经过[编辑]

1986年10月16日早上,[1] 美国选手 Tommie Smith 以世界纪录19.83秒赢得200公尺赛跑。澳洲选手 Peter Norman 以20.06秒获得第2名,而美国选手 John Carlos 以20.10秒的成绩获得第3名,比赛结束后 , 3名得奖者到颁奖台,并由David Cecil,颁奖.两名美国选手在只穿黑色袜子的情况下领奖,代表黑人贫困.[2] Smith 在脖子上戴著围巾,代表著黑色的骄傲, Carlos had his tracksuit top unzipped to show solidarity with all blue-collar workers in the US and wore a necklace of beads which he described "were for those individuals that were lynched, or killed and that no-one said a prayer for, that were hung and tarred.

| 这个用户是一名新手。

若是这个用户不慎犯下任何错误,请秉持假定善意。 倘若在讨论中此用户长期未回应,可能是由于不熟悉维基百科内各功能的操作方式。 |

" It was for those thrown off the side of the boats in the Middle Passage."[3] All three athletes wore Olympic Project for Human Rights (OPHR) badges after Norman, a critic of Australia's former White Australia Policy, expressed empathy with their ideals.[4] Sociologist Harry Edwards, the founder of the OPHR, had urged black athletes to boycott the games; reportedly, the actions of Smith and Carlos on October 16, 1968[1] were inspired by Edwards's arguments.[5]

The famous picture of the event was taken by photographer John Dominis.[6]

Both US athletes intended to bring black gloves to the event, but Carlos forgot his, leaving them in the Olympic Village. It was Peter Norman who suggested Carlos wear Smith's left-handed glove. For this reason, Carlos raised his left hand as opposed to his right, differing from the traditional Black Power salute.[7] When The Star-Spangled Banner played, Smith and Carlos delivered the salute with heads bowed, a gesture which became front-page news around the world. As they left the podium they were booed by the crowd.[8] Smith later said, "If I win, I am American, not a black American. But if I did something bad, then they would say I am a Negro. We are black and we are proud of being black. Black America will understand what we did tonight."[2]

Tommie Smith stated in later years that "We were concerned about the lack of black assistant coaches. About how Muhammad Ali got stripped of his title. About the lack of access to good housing and our kids not being able to attend the top colleges."[9]

国际奥林匹克委员会的回复[编辑]

国际奥林匹克委员会(IOC)主席 艾弗里·布伦达治 认为这是国内政治声明并不适合奥运会的非政治性国际论坛。他命令史密斯和卡洛斯暂停美国队并被禁止进入奥运村,以此来惩戒他们的行为。当美国奥林匹克委员会拒绝时, 布伦达治威胁要禁止整个美国田径队。而这种威胁导致两名运动员被驱逐出了奥运会。[10]

一个国际奥林匹亚委员会的发言人说 史密斯 和 卡洛斯 的行为是“ 蓄意和暴力地违反奥林匹克精神的基本原则。”[2] 布伦达治,于1936年担任美国奥林匹克委员会的主席,在柏林奥运会期间没有反对对纳粹致敬。他争辩当国家对纳粹致敬时,在国际竞赛中是被接受的,但运动员并不代表一个国家,因此不被接受[11]

即使在第二次世界大战爆发之后,布伦达治 被指认为美国最著名的纳粹同情者之一,而他还被国际奥委会主席任命为是奥林匹克人权项目的三个目标之一。[12]

2013年,国际奥委会官方网站声称,“除了得到奖牌之外,美国黑人运动员还因透过种族抗议活动为自己命名。”[13]

|

后果[编辑]

史密斯和卡洛斯在很大的程度上受到美国体育界的排斥与批评。 ‘时代’杂志于1968年10月25日写道:“更快,更高,更强”是奥运会的座右铭。而“更愤怒、凶恶、丑陋”比较适合描述上周墨西哥城发生的情景。[14][15] 回到家乡后,他们和家人都受到了虐待以及死亡威胁。[16]

史密斯 继续参加田径比赛,还跟辛辛那提孟加拉虎队一起参加了国家美式足球联盟比赛[17] ,之后又成为奥伯林学院体育助理教授。 1995年,他在巴塞隆纳世界室内锦标赛上帮助指导了美国队。 1999年,他被颁获加州黑人运动员千禧奖。 而他现在则是一个公众演说家。

卡洛斯的职业生涯也走上了类似的道路。 第二年,他打破了100码短跑世界纪录。 卡洛斯也曾尝试职业足球,是1970年国家美式足球联盟选秀中的第15轮选秀,但是膝盖受伤限制了他与费城老鹰队的比赛。[18] 然后,他进入了加拿大足球联赛,在那里他为蒙特娄云雀队打了一个赛季。[19] 他在20世纪的70年代末陷入困境。 1977年,他的前妻自杀,导致他陷入萧条时期。 [20] 1982年,他受雇于组织委员会还参加了1984年洛杉矶夏季奥运会,以推广奥运会,并与该市的黑人社区联络。 1985年,成为棕榈泉高中的田径教练。 截至2012年,卡洛斯还在该校担任顾问。[21]

史密斯和卡洛斯在2008年的年度卓越运动奖颁奖典礼上获得阿什勇气奖,以表彰他们的行为。[22]

同情竞争对手抗议的诺曼受到澳大利亚媒体保守派的批评。 澳大利亚厨师团长Julius Patching很开心,半开玩笑地私下告诉诺曼,他们说:“他们在为你的血液尖叫,所以请严厉训斥你自己。现在你有得到今天曲棍球的门票了吗?”[23]尽管已经获得了13次资格,他还是没有被选中参加1972年夏季奥运会。[7] 事实上,自1896年现代奥运会开始以来,澳大利亚并没有向1972年的奥运会派出任何男性短跑运动员。[24] 当诺曼在2006年去世时,史密斯和卡洛斯在他的葬礼上都是护柩者。[25]

澳大利亚官员表示他们在1968年的比赛中支持诺曼,没有惩罚他,并且一直认为他是“我们最好的奥运选手之一”。[26] 诺曼在1970年英联邦运动会上代表澳大利亚,并在1972年奥运会之前因膝盖受伤而严重影响了他的表现。[27]

2012年,澳大利亚正式向诺曼道歉,一名国会议员告诉议会,诺曼的手势“是一个英雄主义和谦逊的时刻,提升了国际上对种族不平等的认识。” [28]

韦恩·科莱特 和 樊尚·马修 在1972年慕尼黑的比赛中举行类似的抗议活动后也被禁止参加奥运会。[29]

纪录片[编辑]

2008年悉尼电影节上有一部名为“致敬”,关于抗议的纪录片。 这部电影是由彼得·诺曼的侄子马特·诺曼编写,导演和制作的。[30]

2008年7月9日,英国广播公司四号播出了由Geoff Small发表的关于抗议的纪录片《Black Power Salute》。在一篇文章中,Small指出,参加2008年北京奥运会的英国队的运动员被要求签署会限制他们发表政治声明权利的条款,但他们拒绝了。[31]

感谢辞[编辑]

在2011年圭尔夫大学的演讲中,加拿大奥林匹克委员会成员,加拿大奥林匹克马术队队长Akaash Maharaj说:“在那一刻,汤米史密斯,彼得诺曼和约翰卡洛斯成为奥林匹克唯心主义活生生的例子。从那以后,他们成为了我这一代的偶像,但他们只能以唯心主义为原则做事而不能选择自己真正想做的。成为比当时奥委会主席更具影响力的人是他们的不幸。”[32]

2016年,华盛顿特区的国家非裔美国人历史和文化博物馆还设有雕像,以纪念运动员这几位运动员的贡献。

圣荷西[编辑]

在2005年, 圣荷西州立大学荣获前学生史密斯和卡洛斯22英尺高的雕像,名为Victory Salute,由Rigo 23创作[33] 这是由一位学生Erik Grotz发起的活动,他说:“一位教我的教授正在谈论这位无名英雄并提到了汤米史密斯和约翰卡洛斯。他说他们为了人民做了一项伟大的贡献,但他们却从来没有被自己的学校尊敬。”这尊雕像位于学校的中心,地点在 37°20′08″N 121°52′57″W / 37.335495°N 121.882556°W,位在 D. Clark Hall 和 Tower Hall的旁边。

那些前来造访雕像的参观者可以站在纪念碑上来加入支援他们的活动。因为彼得诺曼没有雕像,所以参观者可以站在他的位置象征性地跟他们站在同一阵线; there is a plaque in the empty spot inviting those to "Take a Stand." Norman requested that his space was left empty so visitors could stand in his place and feel what he felt.[34] The bronze figures are shoeless but there are two shoes included at the base of the monument. The right shoe, a bronze, blue Puma, is next to Carlos; while the left shoe is placed behind Smith. The signature of the artist is on the back of Smith's shoe, and the year 2005 is on Carlos's shoe.

The faces of the statues are realistic and emotional. "The statue is made of fiberglass stretched over steel supports with an exoskeleton of ceramic tiles."[35] Rigo 23 used 3D scanning technology and computer-assisted virtual imaging to take full-body scans of the men. Their track pants and jackets are a mosaic of dark blue ceramic tiles while the stripes of the track suits are detailed in red and white.

In January 2007, History San Jose opened a new exhibit called Speed City: From Civil Rights to Black Power, covering the San Jose State athletic program "from which many student athletes became globally recognized figures as the Civil Rights and Black Power movements reshaped American society."[36]

Sydney mural[编辑]

In Australia, an airbrush mural of the trio on podium was painted in 2000 in the inner-city suburb of Newtown in Sydney. Silvio Offria, who allowed the mural to be painted on his house in Leamington Lane by an artist known only as "Donald," said that Norman, a short time before he died in 2006, came to see the mural. "He came and had his photo taken; he was very happy," he said.[37] The monochrome tribute, captioned "THREE PROUD PEOPLE MEXICO 68," was under threat of demolition in 2010 to make way for a rail tunnel[37] but is now listed as an item of heritage significance.[38]

West Oakland mural[编辑]

In the historically African-American neighborhood of West Oakland, California there was a large mural depicting Smith and Carlos on the corner of 12th Street and Mandela Parkway.

Above the life-sized depictions read "Born with insight, raised with a fist" (Rage Against the Machine lyrics); previously it read "It only takes a pair of gloves."[39] In early February 2015, the mural was razed.[40]

The private lot was once a gas station, and the mural was on the outside wall of an abandoned building or shed. The owner wanted to pay respect to the men and the moment but also wanted a mural to prevent tagging. The State was monitoring water contamination levels at this site; the testing became within normal levels "so the state ordered the removal of the tanks, testing equipment, and demolition of the shed."[41]

Music[编辑]

瑞典国家乐团Nationalteatern在其1974年的专辑“Livetärenfest”中的歌曲“John Carlos先生”讲述的是该事件及其后果

讨伐体制乐团(Rage Against the Machine)在“Testify”单曲上使用了封面艺术品上的敬礼照片(2000)[42]

美国说唱歌手肯德里克·拉马尔(Kendrick Lamar)的单曲“HiiiPoWeR”(2011)的封面艺术作品展示了敬礼的裁剪照片

由美国说唱歌手Earl Sweatshirt创作的歌曲“Hoarse”(2013)的特色是“尖锐的尖峰,拳头紧握,模仿'68奥运会”

“O.J.的故事”的音乐录影带(2017年)由美国说唱歌手Jay-Z描绘了抗议活动

Peter Perrett的歌曲“Shivers”,最著名的是The Only Ones的主唱,其特色是“自由的火炬,Tommie Smith的黑色手套”

美国嘻哈乐团A Tribe Called Quest的“The Space Program”(2017)音乐录影带以Pharrell Williams模仿敬礼为特色

Works[编辑]

- John Carlos故事:改变世界的体育时刻,作者:John Carlos和Dave Zirin,Haymarket Books(2011)ISBN 978-1-60846-127-1

- 三个骄傲的人(2000)[壁画]。 39 Pine Street Newtown NSW Australia.[43]

See also[编辑]

- 20世纪60年代主题

- 1972年奥运会黑色力量致敬

- 奥运会丑闻和争议

- 道格罗比

- 符拉迪斯拉夫·科扎基维茨(Kozakiewicz)的手势

- 杰西欧文斯

- 美国国歌抗议

References[编辑]

- ^ 1.0 1.1 1968: Black athletes make silent protest (PDF). SJSU. [9 November 2008]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于18 December 2008).

- ^ 2.0 2.1 2.2 1968: Black athletes make silent protest. BBC. 17 October 1968 [9 November 2008]. (原始内容存档于17 January 2010). 已忽略未知参数

|df=(帮助) - ^ Lucas, Dean. Black Power. Famous Pictures: The Magazine. 11 February 2007 [9 November 2008].

- ^ Peter Norman. Historylearningsite.co.uk. Retrieved on 13 June 2015.

- ^ Spander, Art. A Moment In Time: Remembering an Olympic Protest. CSTV. 24 February 2006 [9 November 2008]. (原始内容存档于21 October 2008).

- ^ Hope and Defiance: The Black Power Salute That Rocked the 1968 Olympics. Life. 14 October 2013 [13 November 2013].

- ^ 7.0 7.1 Frost, Caroline. The other man on the podium. BBC. 17 October 2008 [9 November 2008]. (原始内容存档于20 October 2008).

- ^ John Carlos (PDF). Freedom Weekend. [9 November 2008]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于December 18, 2008). 已忽略未知参数

|df=(帮助) - ^ Smith: 'They tried to make it a moment, but it was a movement'.

- ^ On This Day: Tommie Smith and John Carlos Give Black Power Salute on Olympic Podium. Findingdulcinea.com. Retrieved on 13 June 2015.

- ^ "The Olympic Story", editor James E. Churchill, Jr., published 1983 by Grolier Enterprises Inc.

- ^ Silent Gesture – Autobiography of Tommie Smith (excerpt via Google Books) – Smith, Tommie & Steele, David, Temple University Press, 2007, ISBN 978-1-59213-639-1

- ^ Mexico 1968 (official International Olympic Committee website. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- ^ The TIME Vault: October 25, 1968. TIME.com. [2016-08-20].

- ^ The Olympics: Black Complaint. Time. 25 October 1968 [12 August 2012].

"Faster, Higher, Stronger" is the motto of the Olympic Games. "Angrier, nastier, uglier" better describes the scene in Mexico City last week. There, in the same stadium from which 6,200 pigeons swooped skyward to signify the opening of the "Peace Olympics," Sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos, two disaffected black athletes from the US put on a public display of petulance that sparked one of the most unpleasant controversies in Olympic history and turned the high drama of the games into theater of the absurd.

- ^ Tommie Smith 1968 Olympic Gold Medalist. Tommie Smith. [9 November 2008]. (原始内容存档于19 October 2008).

- ^ Tommie Smith. biography.com

- ^ Ray Didinger; Robert S. Lyons. The Eagles Encyclopedia. Temple University Press. 2005: 244–. ISBN 978-1-59213-454-0.

- ^ John Carlos. [16 October 2016].

- ^ Amdur, Neil. Olympic Protester Maintains Passion. New York Times. 10 October 2011 [11 October 2011].

- ^ Dobuzinskis, Alex. Former Olympians: No regrets over 1968 protest. Reuters. 21 July 2012 [13 December 2012].

- ^ Salute at ESPYs – Smith and Carlos to receive Arthur Ashe Courage Award. espn.com. 29 May 2008 [17 January 2009]. (原始内容存档于5 April 2008). 已忽略未知参数

|df=(帮助) - ^ Carlson, Michael. Peter Norman - Unlikely Australian participant in black athletes' Olympic civil rights protest. The Guardian. 5 October 2006 [23 August 2016].

- ^ Hurst 2006

- ^ Flanagan, Martin. Olympic protest heroes praise Norman's courage. The Sydney Morning Herald. 6 October 2006 [9 November 2008].

- ^ Peter Norman not shunned by AOC. Australian Olympic Committee. [23 August 2016].

- ^ Carter, Ron. Peter may have lost team place (PDF). The Age. 27 March 1972 [23 August 2016].

- ^ Parliament Apologises to Peter Norman. andrewleigh.com. [April 3, 2018].

- ^ Johnson Publishing Company. Jet. Johnson Publishing Company. 1973: 32.

- ^ 2008 Program Revealed!. 8 May 2008 [17 January 2009]. (原始内容存档于25 January 2009).

- ^ Small, Geoff. Remembering the Black Power protest. The Guardian (UK). 9 July 2008 [9 November 2008].

- ^ Speech to the Ontario Equine Center at the University of Guelph, Akaash Maharaj, 27 May 2011

- ^ Slot, Owen. America finally honours rebels as clenched fist becomes salute. The Sunday Times (London). 19 October 2005 [9 November 2008].

- ^ Part 2: John Carlos, 1968 U.S. Olympic Medalist, On the Response to His Iconic Black Power Salute. Democracy Now!. 12 October 2011 [8 October 2015].

I would like to have a blank spot there and have a commemorative plaque stating that I was in that spot. But anyone that comes thereafter from around the world and going to San Jose State that support the movement, what you guys had in '68, they could stand in my spot and take the picture.

- ^ Crumpacker, John. SF GATE - Olympic Protest.

- ^ Speed City: From Civil Rights to Black Power. History San José. 28 July 2005 [9 November 2008]. (原始内容存档于December 6, 2008). 已忽略未知参数

|df=(帮助) - ^ 37.0 37.1 "Last stand for Newtown's 'three proud people'" by Josephine Tovey, The Sydney Morning Herald, 27 July 2010

- ^ Heritage Assessment of the Three Proud People mural 2012 互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期October 2, 2013,.. (PDF). Retrieved on 13 June 2015.

- ^ It Only Takes a Pair of Gloves Mural. oaklandwiki.org

- ^ West Oakland Mural Bulldozed | bayareaintifada. Bayareaintifada.wordpress.com (3 February 2015). Retrieved on 2015-06-13.

- ^ West Oakland Mural Bulldozed.

- ^ Tropes in Media – The Clinched Fist - GD 203. go.distance.ncsu.edu.[永久失效链接]

- ^ https://www.clovermoore.com.au/three_proud_people_mural

External links[编辑]

- “虚伪的政治” - 包括1968年11月6日“哈佛深红”的授权摘录

- “Matt Norman,导演/制片人'Salute'”(播客:Peter Norman的侄子讨论关于Norman在Black Power致敬中的角色的新纪录片)

- “El Black Power de Mexico:40añosdespués”(布宜诺斯艾利斯的DiarioLaNación,2008年11月10日)

- “这是我的决定”(Tommie Smith谈到他的无声抗议,2008年8月8日)

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||